How does it work?

The word autolyse means “dough breaking itself.” Autolyse should not be confused with bulk fermentation since both serve different purposes, despite some similarities regarding enzymatic activity.

Although yeast may be added during autolyse (not common), fermentation is not the objective. Addition of yeast to the dough undergoing autolysis depends on several factors including processing conditions, dough system and the type of yeast being used.

During autolyse process, several events can occur in the pre-mixed water/flour mixture:

- Continued flour hydration. Water molecules work their way into damaged starch, intact starch granules and proteins.

- Protein bonds continue to develop as a consequence of the “water-rich” environment, creating more gluten strands in the absence of mechanical work. This leads to better gluten structure and gas retention.

- Flour enzymes (mainly proteases) acquire time to adapt and work on the gluten by breaking down protein bonds.Protease activity is higher at low pH (acidic conditions). This is why autolysed doughs that contain yeast or pre-ferments (e.g. poolish) often experience greater protease activity. Such doughs are more extensible, weaker, softer and show less resistance to deformation than autolyzed non-fermented doughs.2

- Finally, as a result, the dough feels less sticky and very smooth after the autolyse.

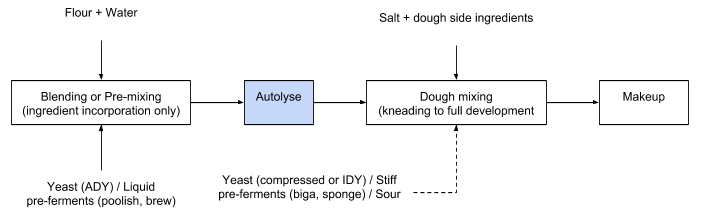

The following block diagram shows the autolyse process:

Application

Autolyse is a versatile process variation that suits the needs of different processes and bakery products. It can be used in the production of French bread, white pan bread, whole wheat bread, croissant dough and brioche. Autolyse is a great option when processing bread formulated with a high percentage of semolina or durum flour. These flours are very strong and contain more protein, so they absorb much more water, producing stiff doughs that require adjustments for optimum makeup.

As a general rule, the longer the autolyse time:

- The shorter the dough mixing time (less mechanical development of gluten-forming proteins in needed). This means less energy consumption during mixing.

- The shorter the dough stability duration

- The less tolerance to overmixing. Breakdown is more pronounced once peak (maximum strength) is attained.

- The smaller the P value in the alveograph test

- The more extensible and less elastic the dough becomes at the end of autolysis

- The better the sheetability and machining of dough during lamination of croissants

- The easier and faster the dough expands during oven spring (better volume)

- The lower the need for dough conditioners

- The better the flavor and aroma of the finished product

Autolyse specifications:

- Blending time: 2–3 minutes at low rpm

- Autolyse time: 20–60 minutes

- Final autolyse temperature: 73–77°F (23–25°C)

- Autolyse equipment: mixing bowl, trough, bench. Product must be covered with plastic or exposed to special RH conditions to prevent drying.

Preferments

Stiff preferments such as sponges do not need to be autolyzed as they have already been hydrated and mellowed by yeast fermentation and enzyme activity.

On the other hand, liquid preferments such as poolish, can be added to the mixture to be autolysed. This is because the high percentage of water in the pre-ferment is needed to properly hydrate the remaining flour and water at dough stage. Fermentation during autolyse (if a poolish is added) would not be a problem given its cold temperature and very low yeast levels.

Yeast

Since the purpose of autolyse does not include fermentation, active dry yeast (ADY) is the only type of yeast that is added to the mixture. Reason is that ADY requires conditioning and mostly remains inactive during the autolyse. By the time the cells are ready (lag phase complete), the autolyse time will be almost over and the fermentation would have been minimal.1

References

- Suas, M. “The Baking Process and Dough Mixing.” Advanced Bread and Pastry. A Professional Approach, Delmar, Cengage Learning, 2009, pp. 51–74.

- Figoni, P. “Gluten.” How Baking Works, 3rd edition, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2011, pp. 136–148.