Origin

Chemical leavening was conceived as an alternative to yeast leavening and long sourdough preparations. Back in the 19th century, the limited knowledge of microbiology and the sensitivity of yeast cells to handling and atmospheric conditions made it difficult for bakers to consistently produce high-quality batches of bread. Further complications such as the absence of commercial refrigeration and hygiene practices made it impossible to properly maintain fresh yeast.

Albert Bird developed the first complete baking powder, created so his wife could still eat bread (she was allergic to yeast and eggs). Rather than using muriatic acid (now commonly known as hydrochloric acid) which was both impractical and dangerous, Bird used tartaric acid in combination with baking soda and a cornstarch filler.

Following Bird, in 1856, chemist Eben Norton Horsford patented the first modern baking powder.2 Horsford originally extracted monocalcium phosphate by boiling animal bones. The monocalcium phosphate acted as an acid that combined with baking soda to create a reaction producing C02. By the 1880s, Horsford’s company switched to mining the monocalcium phosphate to lower costs.2 He placed the two ingredients together in one container, adding cornstarch to soak up moisture, which prevented the ingredients from reacting prematurely.2 The company he created became known as Rumford.

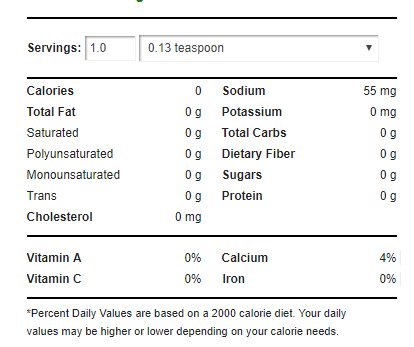

Nutrition

Baking powder has the following nutritional panel:3

Function

Baking powder, when hydrated, will aerate the dough or batter. The aeration provides a light, porous cell structure and fine grain. Also a texture with desirable appearance, along with palatability, to baked goods.1

Commonly used leavening acids in baking powder are MCP, SAPP, SALP, SAS, and tartaric acid. These may be used individually or in combination. MCP is fast-reacting so it is often combined with a slower-acting leavening acid, like SAPP, SALP, or SAS. An example reaction is shown below:

NaHCO3 + H+ = Na+ + CO2 + H2O

Sodium bicarbonate + Acid = Sodium + Carbon Dioxide + Water

Baking powder is classified according to its reaction rate:4

- Fast-acting systems such as sodium bicarbonate-cream of tartar react quickly once hydrated, making their use limited in industrial settings.

- Slow-acting baking powders typically use a combination of sodium bicarbonate and sodium acid pyrophosphate where gas evolution is minimal once hydrated. The majority of the reaction takes place during the baking stage (where temperature is elevated).

- Double-acting systems consist of a mixture of acids, such as sodium aluminium sulfate (SAS) and monocalcium phosphate (MCP). Typical applications of double-acting leavening include products that are baked at home such as biscuits, pancakes, waffles and muffins.

Fillers are used in addition to the active components to make the ingredient shelf-stable. The most common filler is corn starch. Corn starch may be augmented with calcium carbonate, calcium sulfate, calcium lactate, or calcium silicate.4 Fillers perform a two-fold function:

- Stabilize the product by keeping the active ingredients apart, thereby preventing premature reaction, in case moisture should find access to the powder4

- Standardize the strength of the powder4

Commercial production

It’s production begins with the raw ingredients.

The process is as follows:5

- Sodium carbonate is produced using the Solvay ammonia process. Ammonia and carbon dioxide are passed through a saltwater solution in an absorption tower. This results in a compound called ammonium bicarbonate, which reacts with the salt to produce sodium bicarbonate crystals and ammonium chloride.

- Bicarbonate crystals are filtered out by centrifuges and washed to remove residual chloride. The material is heated and reacted with carbon dioxide to produce sodium carbonate.

- Sodium carbonate is then dissolved, carbonated, and cooled, which results in crystallized sodium bicarbonate.

- Phosphate leavening acids are produced from phosphate ore. The base material is either heated and then dissolved (dry process) or treated with sulfuric acid and then purified (wet process) to produce phosphoric acid.

- To create sodium acid pyrophosphate (SAPP), phosphoric acid is partially neutralised to create monosodium phosphate. This is then dehydrated at ~250°C/482°F to form SAPP.

- SAPP and sodium bicarbonate are blended with a filler such as cornflour. Industrial mixers combine the powders into a single, homogeneous blend.

Application

A baking powder may be single- or double-acting. Double-acting means that it contains a combination of leavening acids that will release gas during mixing and again during baking. Alternatively, single-acting baking powders will produce one continuous stage of gas release during the process, the rate of which is determined by the reaction speed of the leavening acid.

There are a variety of baking powders on the market, allowing for use in a wide range of applications. Things to consider when choosing a baking powder are reaction time, process tolerance, single- vs. double-acting in relation to the product and process, and baking temperature/time for the product.

The dosage rate for baking powder can vary significantly depending on the product and the particular qualities desired in the finished bake. A typical cake recipe will use 3-5% baking powder on flour weight, whereas scones may require over 6% on flour weight. Using too much will result in a bitter-tasting product, large bubbles, and surface blistering. Using too little will result in a tough, dense crumb with little volume.

You can make your own baking powder by combining 15ml/1 tbsp bicarbonate of soda with 30ml/2 tbsp cream of tartar.6

Bases and acids used for chemical leavening:

| Bases |

|

| Acids |

|

| Baking powder |

|

Creating a leavening reaction

When creating a leavening reaction it is crucial to know the neutralizing value to avoid an unbalance in the formula. The neutralizing value (NV) is defined as the parts (by weight) of baking soda necessary to release all the carbon dioxide by 100 parts (by weight) of a leavening acid. For example, in the case of baking soda (sodium bicarbonate, NaHCO3), NV is expressed as:

NV = g of NaHCO3 neutralized by 100 g leavening acid

| Typical NV values | |

|---|---|

| Tartaric acid | 116 |

| MCP | 80 |

| AMCP | 83 |

| SAPP | 72 |

| SALP | 100 |

| SAS | 100 |

FDA regulations

CFR Title 21 Sec. 182.1 lists baking powder as generally recognized as safe (GRAS) when used in accordance with good manufacturing practices.7

References

- Chung, F.H.Y. “Bakery Processes, Chemical Leavening Agents.” Wiley Online Library. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 4 December 2000. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/0471238961.0308051303082114.a01/abstract. Accessed 22 August 2017.

- Panko, B. “The Great Uprising: How a Powder Revolutionized Baking.” Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution, 20 June 2017. www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/great-uprising-how-powder-revolutionized-baking-180963772/. Accessed 22 August 2017.

- “Calories in baking powder.” Baking Powder Nutrition Facts, Baking Powder Calories, Nutritional Information. Under Armour. www.myfitnesspal.com/nutrition-facts-calories/baking-powder. Accessed 22 August 2017.

- Pyler, E.J. Baking Science & Technology. 3rd ed., vol. 2, Sosland, 1988. 931-933.

- “Baking Powder.” How Products Are Made. www.madehow.com/Volume-6/Baking-Powder.html. Accessed 22 August 2017

- “Baking Powder.” What’s Cooking America. 15 December 2016. https://whatscookingamerica.net/Q-A/BakingPowder.htm Accessed 22 August 2017.

- US Food and Drug Administration. “CFR – Code of Federal Regulations 21CFR182.1.” 1 April 2016. www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=182.1. Accessed 18 August 2017.